Summary

There is no doubt that strong financial management of a radio station is paramount to its survival, whatever type of station it is. BBC stations have to show that they use their licence fee income effectively, community stations need to generate and manage income from different sources to meet their aims and maintain independence and as Keith states, in commercial radio:A primary objective of the station manager is to operate in a manner that generates the most profit , while maintaining a positive and productive attitude among station employees.In this chapter we will first look at the importance of fixed and variable costs in radio management and how these can impact on the delivery model of the station. We will then consider the importance of costs and cash flow, particularly with regard to establishing a new radio station before moving on to consider how income and costs may be estimated and the potential sources of revenue for a radio station. We then move on to consider how advertising, sponsorship and subscription are forms of income alongside license fees and how community stations face a particularly demanding job raising money for training and community participation on top of the usual station running costs.

(Keith 2004: 56)

Fixed Costs in Radio

In many industries a down-turn in sales may be off-set by a proportional drop in the amount spent on raw materials and labour but in broadcasting it does not cost appreciably less to produce the same programmes for an audience of a few thousand than it does for a million listeners. A popular radio brand does not have to spend a great deal more on raw materials or staff than another with few listeners.The costs of running a radio station tend to remain constant in the short term regardless of changing market forces, and are not directly related to the popularity of the service. In the case of the BBC the current licence fee settlement will run for a number of years and the corporation decides how to divide a fairly predictable income between its various services over that period, setting a budget for each. The funders of a community radio service are largely philanthropic in nature and, usually given a lack of precise audience data, unlikely to be directly influenced by changing popularity of different programmes.

It can be seen that, whatever the proposed funding model, it is possible for management to define a fairly precise budget for the costs of their service at the outset, separately considering whether their income over time will make that service sustainable. We will take the issues in this order.

Fixed and Variable Costs of a radio service

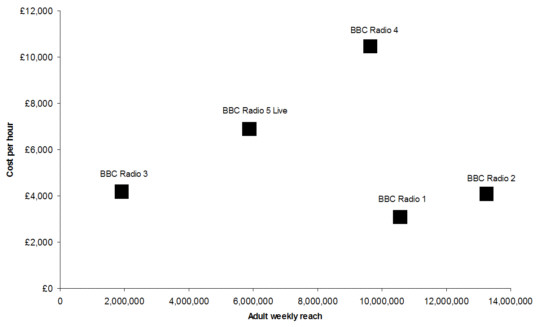

The relative costs of producing different kinds of radio are starkly illustrated with reference to the BBC's expenditure on different national radio networks. The BBC Annual Report and Accounts for the period 2006/2007 (BBC 2007:72) gave the cost per hour of BBC-originated programmes for each radio service as:Radio 1 £3,100Perhaps, more than anything else, this illustrates that the largest factor determining the cost of radio production today is the number of people required to originate an average hour of the service. The fixed costs of studio facilities, distribution and transmission are very similar for different genres of radio but a service heavy in live music, original drama or worldwide news coverage will spend considerably more on musicians, actors, writers, production staff and journalists than one generated by a computer or a single DJ. People are thus the main variable cost for radio production today. We should not be surprised that, when a station finds its income inadequate to cover outgoings, the first items to be axed or severely cut-back are original production and news coverage.

Radio 2 £4,100

Radio 3 £4,200

Radio 4 £10,500

Radio 5 Live £6,900

Plotting the hourly costs of the five BBC networks against their audience figures in the same period clearly illustrates the commercial case for the recorded music based programming in the lower right quadrant of the chart:

Relative costs and audience size of five BBC national networks.

(Sources: BBC Annual Report and Accounts 2006/2007 and Rajar period ending 25 March 2007)

Prior to establishing any serious new radio project it is essential to prepare a business plan, firstly identifying realistically the expected costs of producing the service, secondly estimating the size and character of the anticipated audience and, lastly, quantifying the income, whether from advertisers, sponsors, other funders or the licence fee. It should go without saying that if the latter does not match or exceed the budget cost figure over the lifetime of the project the proposition will need to be reconsidered.

Capital costs

One-off capital expenditure may legitimately be written off in the accounts over a period of years. While the station must find the cash to purchase capital items or pay for the work at the outset, a proportion of the expenditure is shown in the profit and loss accounts across several years as the item is used and depreciates in value. In the case of equipment and building work the period may be up to the expected lifetime of the item. The cost of converting a building might be written off over the whole period of the licence, while it is customary to write off items which require regular replacement, like cars and computers, over just two or three years. In order to facilitate such standard accountancy practices it is usual to identify capital expenditure budget separately from on-going operational costs.Operating costs

Broadcasters previously experienced in operating only pirate or temporary stations frequently underestimate both the amounts that must be set aside for, and indeed the sheer diversity of, operating costs. Costs are usually set out under departmental headings: Programming; News; Sales; General Overheads; Administration; Technology; Commercial Production; Marketing; Research; Training; and financial costs such as bank charges, interest, taxation and depreciation. As a typical example the list of detailed costs under programming might include:Salaries. Full and part time.It is customary to show in the cost budget the entire expenditure on areas such as sponsored competitions, promotions and commercial production even though they may be often directly charged to outside sponsors and clients. The balancing, and ideally greater, income against these headings may then be shown correctly in the station's income projections.

Employers National Insurance contributions

Contract presenters

Freelance contributors

Music purchased

Acquired programming

Consumables

Jingles, on-air branding

Newspapers, magazines, internet

Research

Weather, traffic and news services etc.

Outside-broadcast costs

Competition Prizes

Vehicle costs

Expenses

Training

Management accounts

Cost headings like those used above may form the basic structure of the station's management accounts, usually generated monthly, and the company's annual accounts, where they are known as the 'profit and loss' position. In the profit and loss accounts a radio station usually shows costs incurred during the month, offset against revenue for activities performed in that month. While the profit and loss report gives a snapshot of the trading performance of the project, in order to fully understand the financial health of the operation it is necessary to also look at two other reports on the accounts; the cash-flow and the balance sheet. Any serious broadcasting project will have access to specialist accountancy advice so we will limit ourselves to a managerial understanding of these reports.The monthly profit or loss of a station does not tell us much about the overall financial position of the project. Among other things we also need to know: how many of the facilities are owned by the company and what they are worth today; are there funds from shareholders as yet unspent; how much money does the company owe to other people or organisations; and how much money is outstanding to come into the company. The balance sheet combines the current trading profit or loss with these to show the overall financial position of the company.

Unfortunately money does not flow in and out of a station's bank account in the orderly fashion suggested by the profit and loss accounts. While some smaller projects may insist on pre-payment for advertising, sponsorship or other sales, and pre-payment is often the norm for new or unreliable advertisers even in the largest stations, it is quite usual for a major advertiser to be given credit and to take, typically, up to 56 days to pay the bill (despite the station's terms and conditions specifying shorter periods or immediate payment).

The critical importance of cash flow may best be illustrated by the launch of a new commercial radio service. In setting up a new service the amount of working capital required is frequently underestimated. In addition to gathering enough cash (from shareholders, funders or a parent body) to pay for the physical equipment and facilities, we may need enough money to run the station for some months before any significant revenue starts to come in. It would be prudent to allow for two months of our budgeted monthly outgoings before the station even starts, a first month on-air where the money only flows outwards, followed by one or two months before all the money due to us arrives. It would not be excessive to provide at least one third of the stations budgeted annual expenditure as working capital which will be eaten up in the pre-operational period and the first year. In reality many new services may take a year or two to become established and to have valid research on which to base their case for funding. Very deep pockets may be required to sustain any new media initiative through these early years.

Cost control

One of the manager's most important duties is the control of costs. It is therefore useful if the budgeted operating costs are grouped under cost centres which correspond to the areas of responsibility of departmental managers. In the case of commercial radio it is perhaps the main role of programme management to produce the required quantity and quality of output without exceeding their budget. Meanwhile the main responsibility of sales management is to maximise net sales revenue (after deducting the direct cost of generating those sales). One team in the station brings the money in, while the other spends, hopefully, slightly less.A manager overseeing a cost centre must be alert to a natural tendency for spending to increase rather than decrease and, particularly during times of change or growth, constantly question whether established cost items are still necessary. A simple example is a newsroom's range of daily newspapers and periodicals where, over time, a need will be identified for additional publications. Seldom, unless specifically asked, would anyone suggest removing a title from the list. Similarly, many radio presenters point out that any growth in the listening figures for their programme must be largely attributed to one thing: the quality of the presenter. It follows, they argue, that they should be appropriately rewarded with an increased programme fee. Of course the opposite is seldom the case, the same presenters lose no time in explaining, following a fall in ratings, that there are many factors influencing the size and character of the audience which are beyond their control. It would, they argue, be grossly unfair to suggest any reduction in the presenter's remuneration in such circumstances.

Income projections

While the income of a BBC or community station may remain at an agreed fixed figure for a year or two ahead, in commercial radio there are no such certainties. In order to estimate the commercial income of a proposed new service a realistic estimate of the size and profile of the audience is required. In the next chapter we describe how a fully-funded licence applicant might undertake detailed field research to determine audience projections but a new entrant with limited funding may take advantage of published Rajar results for any similarly sized established stations running a comparable format. An initial model upon which to base a rate-card can be developed by simply scaling these results up or down. The new entrant must however bear in mind that the existing station may have taken many years to establish its popularity and that an over-optimistic audience projection can make life very difficult later, when the station's backers and clients see considerably lower audience figures.It is possible to forecast the likely advertising income of a conventional service using certain standard industry-wide assumptions which, while not statistically robust, have stood the test of time. Ofcom commercial licence applicants are expected to perform this exercise in order to complete the application form. Taking the adult population living in the Total Survey Area (TSA) and projected weekly reach and average hours listened figures we can make an estimate of what annual revenue might be feasible. Here is a typical calculation using hypothetical round figures:

TSA population (Adults 15+) =1,000,000

Projected weekly reach (%) = 20%

Weekly reach (number of adults15+) = 200,000

Projected average hours listened (per listener per week) = 10

Therefore total hours listened (per week) = 2,000,000

Now we must estimate over how many hours each day we will sell effective advertising. The majority of the total listening hours will probably be achieved between 6 am in the morning and late in the evening and few advertisers want their spots to go to air outside this window. For the purposes of this example, assume that we regard this as18 hours per day, 126 hours per week. Conventionally broadcasters estimate that around 95 per cent of the total listening of 2,000,000 will occur during these popular hours, or 1,900,000 hours per week.

The average hourly audience within our 18 hour day = (2,000,000 x 95%) divided by 126 hours = 15,079 listeners per hour

Major advertisers, and particularly their advertising agencies, often compare the effectiveness of different advertising outlets according to the "cost per thousand", how much each medium charges to place their message in front of a thousand of their target consumers. Using "cost per thousand" (cpt) figures currently achieved by similar stations currently for a standard 30-second commercial, and an assumption about how many spots we will broadcast in each of those 18 hours, we can work out our possible annual revenue. For instance if we use an imaginary, but feasible, cpt of £1.20 per thousand listeners and assume that we sell four minutes (eight 30-second spots) of advertising in the average hour:

Cost per thousand for a 30-second spot = £1.20

Average hourly audience 0600 to midnight = 15,000

Therefore average revenue per spot = £18

Advertising revenue per hour (8 spots) = £144

Advertising revenue per day (18 hours) = £2,592

Therefore: Annual Advertising Revenue = £946,080

An alternative but less exact method of calculating likely revenue is to look at the published weekly total hours figure for a comparable station in Rajar and find out their total annual advertising revenue. Dividing the total annual revenue by the weekly total hours will give us an anticipated "yield" figure per weekly hour listened. Lets say we derive a yield of 50 pence per year per weekly listening hour, then the equivalent calculation might look like this:

TSA population (Adults 15+) = 1,000,000

Weekly reach (%) = 20%

Weekly reach (Adults 15+) = 200,000

Average hours listened (per week) =10

Therefore total hours listened (per week) = 2,000,000

Assumed advertising yield = 50p

Therefore total annual advertising revenue = £1,000,000

The annual revenue predicted will be achieved only if, in practice, you are able to sell the assumed number of spots to enough willing clients. Taking the first calculation above, if we assume that there are eight spots on-air in the average hour for 18 hours every day, then a total of 144 commercial spots will be aired each day; 1008 per week. Typically advertisers book a campaign of perhaps five or six spots per day so for 1008 spots we need at least 24 separate advertisers at any one time, each using 42 spots per week. We must convince ourselves that this in achievable target!

The rate card

While few radio sales professionals use a formal rate card in their negotiations with clients it is sensible for the station to have a formal basis for its advertising sales policy. If, for example, we are to achieve a net average income of £18 per spot our asking price would need to be higher to allow for negotiation and provide a margin to pay commission to any advertising agency (typically 15%); a quoted rate of at least £22 per spot would be more appropriate. To regulate demand at various points in the schedule we could price spots higher and lower than this figure, reflecting the relative popularity of our service at different times, and on different days at weekends.Commercial broadcasters frequently divide the day into convenient segments for advertisement pricing and scheduling purposes. It can be convenient to adopt the dayparts used by Rajar (2008) in reporting audiences, on weekdays these are:

Breakfast peak 0600 - 1000

Mid morning 1000 - 1300

Afternoon 1300 - 1600

PM Drive 1600 - 1900

Typically the spot rate for afternoons might be one third to one half that of breakfast peak time, reducing proportionally for evenings and again for overnight. It is usual to levy a surcharge of up to 100 per cent if the client wishes their spot to be broadcast at a specified, fixed, time. Otherwise spots are scheduled anywhere within the chosen time band at the station's discretion.

For many clients a package of spots going out in various guaranteed time bands across the week will be attractive. A typical example is the Total Audience Package (TAP) offered by many stations. This may give the client, say, 35 or 42 spots per week evenly rotated through all day parts, although such packages may omit overnight or when the station may not carry local programmes.

Rate-card prices are usually quoted on the basis of 30-second commercials as this has traditionally been regarded as the "standard" length of commercials in the UK. Rates for other lengths of commercials are commonly quoted relative to the 30 second rate, for example:

10 seconds = 50%

20 seconds = 80%

30 seconds = 100%

40 seconds = 130%

50 seconds = 165%

60 seconds = 180%

A reduction for bulk is often offered but often only for those booking a month at a time. If the average 30 second spot on our station is priced at £22 then a 35-spot TAP might be priced at £700 for one week, or perhaps £2,520 for four weeks, equivalent to an average spot rate of £18.

Larger groups with national coverage use more complex inventory management systems to price and allocate their airtime. While these are beyond the scope of the present book the underlying principles to maximise the income from all available airtime remain the same. At a simpler level many local stations offer smaller advertisers a package such as Image Plus (New Revenue Solutions 2008) where unused inventory is made available more cheaply in return for a flexible commitment to 12 months of airtime.

Cost of sales

New entrants to the radio business often under estimate the amount of sales effort required to attract an adequate level of income to their service. Media advertising is a fiercely competitive field and few advertisers spontaneously contact a radio station to buy airtime. It typically takes at least three face-to-face visits by trained, motivated sales professionals before an advertiser signs a contract. Thus there is an impetus to give clients inducements to book four-week rather than one-week campaigns or to sign-up for three, six or twelve months since the cost of sales can be reduced by selling fewer, longer contracts. Sales staff should still visit the client regularly throughout the contract period, but it is far easier to service an existing client than to start from scratch with a new one.It is customary for individual sales staff to be targeted to achieve a certain level of sales each month and, upon reaching or exceeding that target, to receive commission of a certain percentage of their total invoiced revenue in that month, usually a few per cent. There may also be fixed bonuses for achieving other specific objectives and in addition, to encourage team work, there is often a further incentive if the whole sales team achieves its total monthly target. A sales manager is often targeted entirely on this team achievement, although they may have their own list of key clients.

Traffic department

A title capable of causing confusion, "traffic" in this case refers to the flow of advertisements onto the air. A great deal of work is involved in keeping track of sales orders and the matching files of audio, scheduling the spots and ensuring the advertiser can be correctly invoiced after transmission. The equivalent of a full-time job on most large stations, in a smaller station traffic may be a large part of the work of a sales administrator or the work may be undertaken centrally for a number of stations in a group.A specialist computer programme may produce a daily advertising log for use in the studio playout system, showing against each scheduled break the audio file number, title and duration of each commercial to be played. In an automated system the playout computer may also report back to the traffic system the spots correctly aired, otherwise whoever is responsible for the transmission of the spots should sign their section of the log to verify that they went out as scheduled, noting the actual time of transmission alongside each break in order that the client may be correctly invoiced.

Commercial Production

When a service sells radio advertising they are not selling "time" in the way a newspaper might be described as selling "space", but rather opportunities for listeners to hear a message. The best airtime campaigns are devised by the station, the client or their agency to achieve a specific objective and decisions about the creative content of the spots go hand-in-hand with the purchasing of the airtime.National or multi-national brands may well handle their advertising through a large advertising agency and recording studios in a big metropolitan centre, the first the station will know of the campaign is when the airtime order appears on the traffic system and an audio file is sent to the studio playout system. On the other hand a small local advertiser may rely on their local station to write and produce their commercial.

While a major group of stations may be able to justify a centralised in-house commercial production unit most stations now use specialist production companies and copywriting services. The costs of equipment, experienced production staff, music fees and voice-over sessions are hard to justify on a station producing perhaps one or two new commercials per day.

Any fee paid to actors or musicians to perform in an advertisement usually permits the broadcast their work on a defined number of stations for a limited period (usually one year). If a client wishes to run the same spot to run on other stations, in the same market or elsewhere they will usually need to pay a higher rate. Equity, the actors union, publishes guidelines for its members based on a sliding scale of minimum rates per commercial depending on the size of the station.

The use of music in commercials is frequently misunderstood, the copyright licence arrangements with Phonographic Performance Limited, the Performing Rights Society and the Mechanical Copyright Protection Society, which give blanket permission to use music in programmes, do not automatically permit the use of their member's music recordings in commercials. The producer must negotiate a separate fee, which can be very expensive, directly with the rights owners, usually the record company and the music publishers, in order to use any part of a record in an advertisement (there can however be a dispensation to use music in an advertisement which is promoting sales of that record or a performance by the artist concerned). To minimse costs commercial producers often purchase libraries of "production music" which they are then able to use in advertisements for a flat fee charged by the producers of such library music.

Sponsorship

Programme sponsorship is a significant additional source of income for today's radio services. According to Ofcom (2007) of the £514 million earned by national and local commercial radio in the UK in 2006, sponsorship generated £91 million (18%).The proportion of total income attributed to sponsorship has increased slowly as rules governing its inclusion in British broadcasting have gradually relaxed. Commercial involvement in programming was frowned upon in the UK and specifically banned at the launch of commercial television in the 1950s, and at the start of legal commercial radio in the 1970s. Even when, in the 1980's, the Independent Broadcasting Authority (IBA) decided that a limited amount of sponsorship might be permitted, for coverage of an event or happening with an existence independent of the broadcaster, they decreed that it be referred to as "co- funding".

Until the provisions of the Broadcasting Act 1990 came into force, programme items were usually described as being "brought to you in association with...", in order to maintain the image of co-funding, and all sponsorship deals had to be approved in advance by IBA officers. Following the 1990 Act the newly established Radio Authority permitted sponsorship provided ultimate editorial control of sponsored programmes remained with the licensee; endorsement of the sponsor's product within editorial was not permitted; sponsorship was clearly acknowledged in at least one credit at the beginning or end of the programme or item, every 15 minutes in longer sequences; and that sponsor credits were brief, precise and capable of substantiation. The Radio Authority Code of Advertising Standards and Practice and Programme Sponsorship said sponsor credits "should sound like acknowledgements, not advertisements." News bulletins were, and still remain, specifically excluded from sponsorship.

Under Ofcom's lighter touch regime sponsorship is handled in the same way as advertising with clearance handled centrally by the industry for certain categories of sponsor and with the same list of services and products forbidden from appearing in advertisements or sponsor announcements. Within the guidelines station managers must decide for themselves what they are, and are not, willing to do for a sponsor: How many references will they receive? Will credits be live, pre-recorded or sung as a jingle? Will they receive additional credits in other programmes promoting their show or feature?

When forecasting the potential for sponsorship income on a particular service it is useful to divide sponsorship opportunities into two categories: firstly those the station will broadcast whether or not they are sponsored and where the whole income goes straight to benefit the station's bottom line. Secondly, those special events or items which the service can afford to include in the schedule only if someone else is paying. The station might like a "flying-eye" helicopter, or an outside broadcast from Paris but will only be able to run them if someone else provides the cash. Before accepting such proposals the prudent manager will always ask whether the income for the new costly activity genuinely represents 'new money' or whether the client will simply deduct it from existing advertising or sponsorship funds which would have come to the station anyway.

Community and other non-commercial broadcasters can face a similar quandary. Much public sector funding of radio is conditional on the production of features to tackle a particular issue; the employment of trainees or the provision of some other specific service to the community. Before accepting such a grant the station management must decide whether, taken overall, the funds will actually contribute to the core objectives of the radio service. It is too common for a community station to be full of staff and trainees few of whom are in any way contributing to the main on- air service. As with the commercial case every attempt should be made to direct funding to support the basic objectives of the radio service before diverting funds onto separate projects, no matter how worthy. (See our Section 3 Case Study of Bradford Community Broadcasting for more detail on this area)

While sales management will usually have the final responsibility for the revenue achieved from the sale of sponsorships and promotions the detailed on-air arrangements must be worked out with, or preferably by, the programmes management team.

Subscription radio

A by-product of radio's move into the digital era is the ability to encode and route signals in a way that was prohibitively expensive in the days of analogue broadcasting. As with television, it is now relatively straightforward to encrypt a broadcast digital radio signal, permitting reception only by those who have paid for it. Other digital platforms, such as those supplied by the internet and 3G mobile telephone technology make possible for the first time programme streaming to registered subscribers.Fans of this new method of funding radio broadcasting argue that a potential advantage of subscription radio is that, as it does not have to rely on advertising revenue, it does not have to chase audience ratings in the same way as commercial stations. It is suggested that one of the main advantages of the XM and Sirius satellite radio systems in the US is that they provide niche programming that could never be provided by commercial radio or BBC networks funded by a universal licence fee and there is now increasing interest in portable and mobile satellite reception systems that work without the expensive network of terrestrial transmitters needed for DAB.

The meteoric growth of satellite radio in the US was documented in the New York Times (2005):

The announcement on Friday by XM Satellite Radio - the bigger of the two satellite radio companies - that it added more than 540,000 subscribers from January through March. Analysts call that remarkable growth for companies charging more than $100 annually for a product that has been free for 80 years.In the USA, where the majority of popular AM and FM stations carry a heavy load of advertisements and there is no nationwide public service alternative the subscription services have a particular appeal. But a number of companies, including Ondas Media and WorldSpace, have been reported to be looking to launch subscription based satellite radio services across Europe in the next few years.

Total subscribers at XM and its competitor, Sirius Satellite Radio, will probably surpass eight million by the end of year, making satellite radio one of the fastest-growing technologies ever - faster, for example, than cellphones.

Ricky Gervais, comedian and co-creator of The Office, is often credited as being one of the earliest examples of a podcaster who made money by selling subscriptions. His first series of podcasts, starting in December 2005, were available free via the Guardian Unlimited website, and the broadcasts were downloaded an average of 261,670 times a week. For seasons two and three, during 2006, Gervais moved to a paid model, charging a subscription of £3.73 for the series or 95 pence for each individual episode.

According to new media consultant Leesa Barnes (2007: 200), while many podcasters like Gervais appeared to have developed a practical subscription model, in reality they had simply moved into audio publishing via the web. Barnes argues that few podcasters have managed to monetise their programming is that the technology to make it happen was originally very complicated, requiring a fairly detailed knowledge of computer programming. Only recently have internet service suppliers begun to offer simple podcasting solutions which are dependent on payment of a subscription fee by the listener and prevent the recipient from sharing their RSS feed with anyone else. According to Barnes (2007: 201) US podcasters are now successfully charging between $1 and $150 per month for subscriptions to their shows.

Ultimately subscription technology may even be seen as offering a more equitable alternative to the universal BBC licence fee - a single licence payment might unlock the full range of BBC content in a household. It may take some time for a public used to receiving radio free of charge to accept the concept of paying for radio at the point of delivery, but not long ago, before Sky TV, the concept of subscribing for a TV service was similarly alien.

Community Radio-thinking outside of the funding box

As long as we in the sector simply sell ourselves as 'radio' or 'media' we are open to being under-cut by our commercial colleagues. Our USP is as a trusted intermediary with the communities that the agencies wish to reach. Community Engagement is popping up more and more as a statutory requirement for public sector bodies and believe me, most are just gasping for an effective way to deliver it.There are now many different models of funding for community stations world wide, each framed by regulations laid down according to each country's broadcasting laws and regulations. Most community stations in the UK have developed a 'mixed economy' approach to funding using grants, advertising, sponsorship and commercial activities, local fundraising (including in-kind and other donations), contracts for public services (Service Level Agreements) and funding relating to the provision of training (Korbel 2008a). It is this variety of sources that contributes to the sustainability of stations.

(Korbel 2008b)

There are arguments for and against using different forms of income generation - all have implications for paid work at the station and the direction the station takes. Some stations (particularly those serving communities of interest) gladly take advertising as they see the local business community as part of their target audience. Others see it as 'a necessary evil' and balance the need for paying sales people and taking up studio time for producing advertisements with other community training and production commitments. Many stations decide not to take advertising in order to concentrate fully on fundraising directly for training community programming.

In order to successfully raise funds for community radio you need to carefully align what you are applying for with the activities that are at the heart of your radio station. It is necessary to 'think outside the box' when it comes to pitching for funds that will contribute to programme making and station activities as Korbel (2008a) says 'The unique selling point of your station is community not radio'. Community radio can be seen as a tool to deliver projects in large number of areas where there is need for community action so a good starting point for each station is to look at areas like health, crime prevention, women's issues, work with young people, rural communities and tie in community radio programme making with this. (See Bradford Community Broadcasting case study in Section 3 for examples of this and also Community Radio Toolkit website for different funding examples). Although general awareness of the advantages of community radio is now higher now that more stations are on air, many potential funders in the voluntary and statutory sectors will not necessarily see the link between community radio and their activities. Therefore it is a prime function of the station management team to forge links with potential funding partners.

Regulations and income sources for community stations

There are several regulations relating specifically to community radio funding that managers should be aware of and will in turn inform a fundraising policy. Some of these rules are complicated and have been controversial Not all stations can take advertising: community radio stations with a coverage area which overlaps by 50% or more with that of a small commercial radio station serving between 50,000 and 150,000 adults will not be allowed to take any advertising or programme sponsorship because it is seen as compromising the commercial radio's business. For those stations that can take broadcast advertising this is limited to no more than 50% of a station's income in any one year. In addition, Ofcom requires that no more than 50% of a station's funding can come from a single source, however since 2008 community radio stations have been able to count volunteer input as part of their turnover. To this end stations are required to report to Ofcom about the balance of their sources of income and there are specific guidelines and guidance provided by Ofcom and Community Media Association websites.Community Radio Fund

When Anthony Everitt evaluated the Access radio stations in 2003 one of his key recommendations was that there should be a fund established to aid in the management of and fundraising for community radio. He recommended that the Community Radio Fund should provide up to 30,000 a year to stations. This has been set up through Ofcom. In the period 2006-7 it made payments to 40 community radio stations, totalling £829,975.44 and in 2007/08 34 community radio stations received a total of £465,015. The Welsh assembly allocated £500,000 to stations in Wales in one year alone. In England the average amount awarded has been about £14,000 and stations have usually received only one payment from the fund. The monies are usually spent on Station Manager or fundraiser posts for a single year. (See below for discussion of this fund).Service Level Agreements (SLAs)

Here stations are funded in return for broadcasting services to statutory or voluntary organisations. This can take the form of public service announcements, podcasts, a set of programmes on a particular theme and multi-target contracts that will have a range of benefits to the users. Stations have negotiated SLA contracts with council and government departments and services, schools, colleges and universities. Drystone Radio In the Yorkshire Dales had a SLA with the National Parks service to produce 8 podcasts of National Park trails in the area (Tang 2008: 38). Forest of Dean Radio have a 3 year SLA agreement with their local council with various targets to be met In return for funding including getting a set number of new voices on air and giving support to community groups through broadcasts (op.cit: 40). A detailed guide to developing and setting up SLA's can be found at http://www.commedia.org.uk/about-community-media/publications/publication- items/service-level-agreements/.Lottery

The National Lottery has schemes such as Awards for All and the Big Lottery Fund Takeover Radio the children's station in Leicester was awarded £5,000 for training 24 young presenters and the Big Lottery Fund granted £368,000 to Prescap Limited for working in conjunction with Preston FM on a project called 'Improving Social Cohesion and Community Capacity through Community Radio'.Other sources that can be looked at include funding for international networks, projects and training programmes via funding from the European Commission's Education, Audio Visual and Culture Executive Agency. The Erasmus and Comenius programmes fund work in conjunction with schools, Leonardo da Vinci with higher education and Grundtvig with vocational education and training and adult education. For further information see http://eacea.ec.europa.eu/llp/index_en.htm

For further information about funding ideas and opportunities see Community Media Association and Community Radio Toolkit websites. See also section 2.10 for more about raising funds for training courses in community stations.

Issues for community radio fundraisers

Raising money for community stations can be a creative process but for most managers it is a constant headache. In fact due to the large number of licences awarded and the relatively small size of the Community Radio Fund it has meant that stations have to work very hard for stability year on year. There has been much lobbying for a larger fund so that more stations can be sustainable. Mary Dowson CEO of Bradford Community Broadcasting says the UK should offer far better support for the community radio sector:Constant fundraising - and the whole amount of associated project reporting - takes up an enormous part of the staff time which could be much better spent on running a radio station and delivering the projects themselves

(Everitt 2003 b: 34)

At a policy level there have been suggestions that the UK should follow the example of the Irish community radio sector which gets funds every year from a 5% levy of the television licence fee (see http://www.bci.ie/broadcast_funding_scheme/index.html) Another option that has been mooted is the French model in which community radio is funded by a percentage of commercial broadcasting's advertising revenues. (See Tacchi and Pryce Davies (2001) for a discussion about different international models of community radio funding)

Go to main page