Summary

In this section we will consider how the performance of a radio station may be managed. We will look at how financial and operational performance may be monitored, reviewed and evaluated and, with respect to operational performance consider particularly how staff may be managed in an appropriate manner. The section will close by considering how a successful station may maintain its performance, how we might turn around the performance of an ailing one and how community radio can contribute to new forms of impact assessment and measurement.Financial performance

As described in section 2.3, the manager will have set out, and agreed, budgets for their area of responsibility. Normally these budgets will be broken down into individual months with figures often varying from month to month to reflect varying activity levels, expected market conditions, or steady growth. A programme manager might have a list of cost centres under their control and will be expected to keep within the agreed overall cost while a sales manager will, in addition to making sure costs remain under control, also have a set of targets for revenue generation. In the case of a community station the manager should know what income is expected from grants and fundraising each month.Budgeting, which normally takes place a month or two before the start of the twelve month period, is not an exact science. It is difficult to forecast exact costs a year ahead, let alone predict other people's spending on advertising. Most senior managers will be tolerant of a small overspend or shortfall in one area under a manager's responsibility if it is compensated by under-spending or exceptional income in another. Similarly a poor result in one month may be compensated by exceptional performance in the next. Nevertheless the aim is to stay as close as possible to the budget overall and to end of the year on target.

Senior managers need to review financial performance at least once every month as any longer interval can lead to a temporary difficulty becoming a problem that cannot be corrected before the end of the financial year. Larger groups will have central accounts departments which constantly gather data from the station and in return supply monthly management accounts and detailed analysis. Independent stations will need to generate their own regular management accounts. Fortunately this need not be as difficult as it sounds. A single radio station is really a very straightforward business and off-the-shelf accounts packages can readily be adapted for radio station use. Most sales traffic software packages will interface with the accounts software, producing monthly invoices for advertisers and automatically adding the transactions to the sales ledger. It is important to be disciplined in entering the data if the accounts are going to provide useful management information: all sales orders should bear a code indicating the sales executive responsible for the sale; all payments to suppliers must be recorded on the system with a code indicating to which cost-centre they should be charged.

In order to produce a clear picture of how well a commercial station is trading, it is customary for income to be shown in the month during which the airtime or service is provided, not when it is sold or when the income is received. Similarly expenditure is shown in the month in which it is incurred, even if payment is received at a later date. It is therefore essential that, at the same time as considering the monthly profit-and- loss management accounts, the manager must review the company's cash position. Paying all bills on time while being lax about collecting income from advertisers and sponsors can lead an apparently profitable station into serious financial difficulty.

The manager must be aware that the average member of staff will not initially understand how to read a set of accounts. The monthly profit and loss report may be clear enough, but the importance of the cash flow, of chasing debtors to collect their cash within a reasonable time and, particularly, of the balance sheet may be lost on many. Comparisons - particularly in both percentage terms and historically - can be very useful and informative. A 10% overspend in one area identified early enough in the financial year can be corrected. An increase year-on-year in line with inflation might normally be expected, anything larger must be justified by a budget for greater or more lavish activity.

All radio station staff should be encouraged by regular monitoring and reporting to keep expenditure below budget. So often, particularly in commercial radio, we see an individual's sales performance being celebrated, usually with the help of a bonus or additional commission, because they have produced income above their target. The manager must remember, and constantly remind staff, that a saving of £1,000 in costs is just good - often even better - than raising another £1,000 in income. But too often production departments will go to great lengths to avoid an under-spend, fearing that their future budget will be cut as a result, or that they might be criticised for not 'pulling out all the stops' if their performance turns out to be inadequate somewhere down the line. Some stations attempt to offset this attitude with staff bonuses, often available only to those not already in a sales bonus scheme, triggered by the profitability of the group, company or, their own unit.

In a commercial setting, local income generation will usually be the responsibility of a sales manager. The manager will have an overall annual target that they will be expected to break down into individual months. Then, within each month, the target total may be split between separate figures for airtime, sponsorship, promotions and commercial production. The division between these headings will be based on local experience, the format of the service and its relationship with its listeners. Finally, within each heading every month, a number of individuals may be responsible for bringing in the revenue. An individual sales executive might therefore have a specific target each month for airtime, sponsorship, promotions and commercial production.

As we described earlier (Section 2.3) it is customary for individuals to be motivated to achieve a certain level of personal sales each month with commission equivalent to a few percent of their total invoiced revenue in that month upon reaching or exceeding that target. In order to encourage teamwork, there is often a further incentive if the whole sales team achieves its total monthly target. In a small station a sales executive might take home an additional, say, 3 per cent of their own sales if they meet their own monthly target and a further 3 per cent of their own sales if the team also achieves its overall target. With typical individual monthly targets in local radio of £10,000 to £15,000 such commission can amount to a significant additional income, although of course it is still subject to tax. The sales manager is often targeted entirely on their overall team achievement, whether or not they may have their own list of key clients.

From time to time there may also be fixed bonuses or incentives for achieving other specific objectives. In some cases, following a temporary period of poor trading, companies permit a quarterly "claw-back" scheme in which the monthly bonuses are payable if a surplus in a later month compensates for the shortfall in an earlier month.

Operational performance

Monitoring and evaluating financial performance is relatively

straightforward but the manager will find evaluating the

performance of creative individuals far more challenging. Not

only is their worth to the station far more subjectively measured

but the demands and expectations of the station may vary from

individual to individual.For the purposes of this book it may be most informative to consider the techniques commonly used to monitor, evaluate and review the performance of radio presenters, and look at how these differ from those used in the sales arena.

While sales managers, almost without exception, hold meetings with their entire team at least weekly, today most experienced programme managers avoid holding group meetings of presenters except to announce matters of company-wide importance, or where all staff are invited. They prefer to schedule regular one-to-one meetings with individual presenters, or perhaps with the team responsible for a co-presented show. This radically different approach reflects not only the more personal, individual, role of the presenter but also their very different personal motivation. A group of presenters often have little in common, in terms of the challenges of their individual work, other than the state of the studio, the headphones and the coffee machine. So it should be no surprise if discussion at any such team meetings generally descends to this level.

The programme manager may privately sit down with the presenter of a daily programme every week (perhaps once each month with the presenter of a weekly programme) for a 'coaching session' based around the playback of a recent programme. The programmer can play a sequence, or perhaps a single link, and then initiate a discussion on how well it was presented and how it could be improved in future. To save time it is common to use a recording with any music tracks edited out. To this end some studios have a dedicated recording system set up to run only when the 'microphone-on' light is illuminated. This conveniently provides a ready- made recording without any music, advertisements or other external or pre-recorded items.

Coaching sessions should always be helpful and supportive, rather than negative and controlling. There is no point in encouraging the presenter to repeatedly brood over an error or misjudgement, far better to highlight and fix in their mind those elements which worked well, or at least those which make their boss happy. For this reason it is often helpful to chose a programme segment at random rather than use this meeting as a post-mortem on the worst of the week's output. Indeed it can be constructive to invite the presenter themselves to choose the segment for review. They may pick a section they are particularly proud of or they may seek input on a particularly challenging part of a previous programme.

Inevitably, despite concerns over the reliability of Rajar data, outlined in Section 2.1, programme managers are regularly called upon to review the performance of individual programmes using the results of audience research. This can be undertaken more fairly and with greater confidence by using comparisons with other known data. Given a set of numbers in isolation, even with the most robust sample, it is not possible to say whether they represent "good" or "bad" programming performance. As we said earlier, any research result should be interpreted in relation to at least one other piece of data, preferably several if the sample sizes are small. In analysing the results for a single programme suitable benchmarks might be:

- Previous performance of this service at the same time and day.

- Performance of competitors' services at the same time and day.

- Performance of comparable programmes, perhaps on similar group-owned stations, at the same time and day elsewhere.

- Overall size of the total radio audience at this time on this day.

- The average audience delivery of this service at all other times.

Many managers believe that trends over three or more surveys are more important than any quarter's individual results. They argue that it takes time for listeners to adapt to any change and that the most recent results probably reflect the audience getting used to changes made a year previously. Experienced programmers know that it can take as short a time as fifteen to twenty seconds for an existing listener to switch off if you offer them something they do not like, conversely it could take fifteen to twenty months before a non-listener becomes a regular listener because of that same programme change!

As in all aspects of a manager's dealings with employees it is important, in discussing research findings, not to dwell on the negatives. In a creative field like programming it is better to seek out the most successful aspects of the schedule, analyse these, praise the people who did well and apply the lessons learned to the weaker points in the day. The manager must avoid spending all their time worrying about the things that apparently did not have the desired result but rather should investigate the items that worked well in as much detail as those that did not. Better to focus the minds of the team on what success sounds like than to endlessly recount their failures.

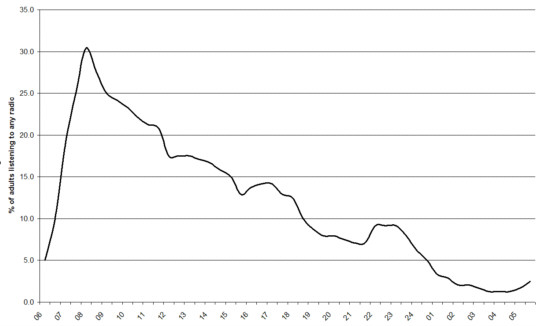

It is useful to bear in mind the natural patterns of radio listenership that have been established over many years. This graph, drawn from a typical mid-range local commercial radio station shows the proportion of the total adult audience in that station's area listening to any radio station at all at different times across the average weekday:

Typical weekday listening pattern: .

This is an instantly familiar pattern to any experienced programme manager. The audience rises rapidly to a peak around breakfast time and then declines, almost linearly across the day until reaching an overnight low around 1 am. There are commonly small bumps in the decline around lunchtime, afternoon 'drivetime' and bedtime, perhaps after the TV is switched off. Given this typical shape to a Rajar curve, the manager should be equally pleased with an afternoon show and a breakfast sequence even where the former achieves half the number of listeners as the latter.

There may be commonsense reasons why a particular format, or station in a specific market, might happily achieve a profile across the day different to this norm, for example where the target listeners can be expected to be unable to listen while at work or school or where the manager has decided not to attempt to compete with strong programming on a rival service at a particular time of day.

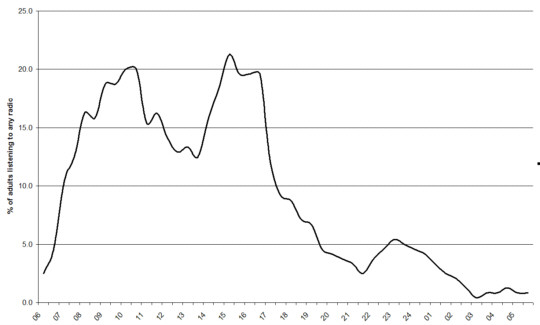

In this respect it is helpful to look at the corresponding radio listening patterns achieved in this same area at weekends:

Saturday listening pattern

In this case on the average Saturday it is possible to discern the same underlying pattern, a breakfast peak, although later than on a weekday, followed by a linear decline across the day. But on to this is superimposed an effect specific to this market, with considerable interest between 3 pm and 5 pm in coverage of the local soccer team. In these circumstances a station carrying a major soccer programme would not worry about a substantial loss of audience after 5 pm, which would not be the fault of the following show.

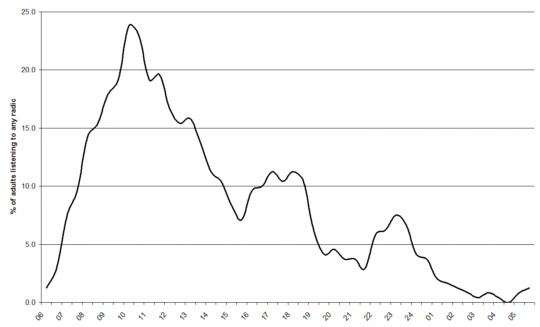

Sunday listening pattern

Looking at Sundays over the same twelve month period in the same area we see the breakfast peak has moved a further hour later, reflecting real life in the typical household. In this case the decline across the day is disrupted by a late afternoon peak for the long established chart shows and again by the local popularity of a late- night phone-in.

Before attempting to interpret their own audience figures managers should always try to understand such local patterns of overall listening. It is one thing to ask a presenter to take a greater share of the available audience in their area at a given time, it is quite another to ask them to create new radio listening.

While quantitative audience research is too blunt a tool for analysing the performance of individual programme elements many of the above principles may be applied to the effective evaluation of staff in other creative areas, in news, production etc. Of greatest importance is an understanding and agreement between the employee and their manager of what level of performance is currently being achieved, what is expected in the future and what has to change in order for them to get there.

In the absence of formal audience research care should be taken in the choice of other indicators of success. It is tempting to judge the popularity or success of a programme or feature by the quantity of audience response it stimulates. But is a 'phone-in which generates a lot of calls necessarily a better programme than one that only has sufficient to get by? Often, as has been demonstrated by the recent wave of premium-rate telephone scandals, the need to encourage the maximum amount of audience response can be detrimental to the long-term interests of the programme. It is quite possible to design a format which will generate the maximum number of texts, emails or telephone calls but which does not present the ordinary radio listener with a satisfying listening experience.

The reader might ask themselves how often they have personally responded to a radio programme or feature and compare this to the number of separate programmes they have actually listened to in their lifetime. Many in BBC local radio have in the past applied a principle that only a certain proportion of listeners will actually take the trouble to respond to any one general programme item. Journalist Max Easterman recalled in a training session from BBC Audience Research he was told that for every letter written, 200 other would have done so if they could have been bothered. (Source: Radio Studies discussion list, November 2008). We have an example of one community radio station which suggested that this sort of 'rule of thumb' can work, Janey Gordon showed how this rule could be applied during research carried out for a student RSL: 'Our audience research indicated an 11 per cent reach of the population (180,000) and we logged 200 calls over 28 days giving a ratio of 1 call to 99 listeners.' (Gordon 2000: 87) however it is difficult to pin down wider research to substantiate this model, which in any event would surely vary from format to format, with different target audiences and at different times of the week. Nevertheless applying it can produce an uncannily accurate estimate of likely response. The point here is that, even if we apply the more optimistic factor of one in a hundred radio listeners being likely to respond, a programme item should always be aimed at the casual, passive, listener rather than the smaller number of actively participating listeners.

In a desperate attempt to find quantitative indicators of programming, marketing or engineering success to match the figures available in the sales and financial arenas, the manager can distort the priorities of their staff. If, for example a journalist finds themselves judged on the number and duration of local stories included in a week's news bulletins are they not more likely, on a quiet news day, to produce items of little interest and relevance to the target audience simply to meet their quota?

We remember being asked to evaluate a daytime programme on one of the first wave of community radio stations, or incremental licence stations, Wear FM. Although well established and creating a great deal of interest the station appeared to suffer from a poor level of regular listening. Monitoring the programme one possible explanation soon became clear. A simple competition to win a CD was promoted to the exclusion of almost all other content over more than two hours of the programme, the straightforward question and studio telephone number being given after virtually every song, news bulletin or feature item. A harmless little bit of fun was extended until it became tedious and boring. After all, there were only four positions the listener was likely to adopt: they knew the answer and rang in straight away; they knew the answer and couldn't or wouldn't ring in; they did not know the answer and were intrigued to find out what it was; or they did not know the answer and did not care. In any of the four cases the listener had a right to expect the solution and identity of the winner to be announced within a reasonably short period of time, or at a stated time in the future. They were not likely to hang on for two hours just to discover the answer to a single general knowledge question. Why was the programme being based around such a flimsy premise, of no relevance to the purpose and objectives of the community radio station?

The answer was to be found off-air. This was many years ago before the widespread adoption of email and texting and most audience response was via the telephone. With a ready supply of voluntary help the station arranged for a volunteer worker to always be stationed in the office fielding every call to the studio, all calls being logged in a big ledger. In the absence of any other form of research the manager had encouraged a culture in which the relative success of each programme was judged by the number of ledger entries it generated. Although not the manager's intention, presenters were effectively encouraged to ruin their programmes for, perhaps, 99 percent of the potential audience in order to maximise the number of calls from the other one percent.

Destroying the ledger and introducing a system of coaching based on the true programming objectives of the station had an immediate effect on the station output, although we will never know how it impacted on audience levels.

Maintaining success

Success brings its own problems for the manager. Not only may the bar be set higher for their performance in the future but complacency can set in. It is a brave act but undoubtedly a great programme manager will not hesitate to evolve and improve an already successful programme schedule in order to preserve that position in the future. Perhaps the most celebrated example in British radio must be the painful reinvention of BBC Radio One in 1993. As Wilby and Conroy point out (1994: 44) after some 26 years the very successful station, launched as a youthful replacement for the pop pirates of the sixties, Radio One had an audience age profile spread across three decades with presenters who had aged with their audience:While the station's branding was relatively unproblematic when it came on air in 1967, its long history as an 'institution' in British radio broadcasting provides an illustration of how a radio station constantly has to rethink brand identity, to respond not only to changes in British culture, listening habits and audiences' self-image, but also to developments in economic thinking and management style within the BBC itself.Following the sudden departure of presenters Simon Bates, Alan Freeman, Dave Lee Travers and others, the station went from a weekly reach of 19.2 million listeners in June 1993 to 14.8 million seven months later. The decline continued in subsequent years, eventually settling at about 10 million, around the level it remains at today.

In an article to mark the fortieth birthday of the station, Colin Garfield writing in the Observer (2004) quoted the current Radio One controller Andy Parfitt defending the need for change:

It was terribly important that it happened, and the Radio 1 that survives and prospers today is a result of setting the foundations then. Nobody talks of privatising Radio 1 now, but back then it was a regular idea, because people couldn't see how we were different from the commercial competition. So the rebranding of Radio 1 - what we stood for - was done in a remarkably potent way, but at a great cost of listeners.Anyone can be brave enough to initiate change in an ailing radio service, the only way is up, but it takes real courage and leadership skills to manage change in a successful operation. But the biggest challenge in managing a successful radio service is in simply defending that position. Suddenly you are the one everyone wants to beat. Not only will your programming and sales tactics be studied and copied by others but your staff will be of greater interest to your competitors. Unless the manager is running the top station and has a limitless budget they must accept that their star performers, in any department, are likely to want to move on from time to time. If for no other reason, standing still is not an option for a successful station. The manager must always be developing new staff and new ideas, ready for the day when they are needed.

For the programme manager the introduction of so much automation and networked programming, while offering great advantages in cost-efficiency, has closed the door to many programme and presenter development opportunities. At one time it was usual for the first rung on the ladder for a new presenter to be an overnight shift – perhaps between 1 am and 6 am, where they could hone their presenting skills without any great risk to the station image. At the same time bold and adventurous new programming ideas could be tested in the late evenings or at off-peak times of the weekend. Today, quite correctly, the emphasis is on putting out the best possible sound at all times, and if the budget requires that this be done using an unattended computer, so be it. Increasingly, therefore, managers are looking outside their station, or even industry for the stars and big ideas of tomorrow. The BBC has never had any reluctance to recruit from commercial stations and commercial stations are now learning to recruit from the new wave of community and internet stations.

All radio stations, all companies and organisations, must evolve to survive. This is particularly true where the technology and competition is changing and expanding as rapidly as in the world of digital audio. A radio station, no matter how successful, is like a leaky bucket, the manager who stops pouring fresh water in the top will very quickly be left with nothing.

Managing an ailing station

In many ways, while not always a pleasant experience, dealing with an ailing station is far easier than defending a successful one. In many cases there is little the new manager can do to make things worse and there is frequently more scope for experimentation and fresh ideas.The key question for a new manager coming into such a situation is whether the staff realise that the station is broken and needs to be fixed. It is far easier to introduce rapid changes in an environment where staff understand that change is not only inevitable but desirable than in one where the manager is constantly told 'we don't do it that way here'. The first task of the incoming manager must therefore be to ensure everyone understands, through group and individual meetings and presentations, the nature and scale of the problem. Having clarified the present position the manager can outline where the station should aim to be in the future and invite ideas to get it there. In this environment the manager's new idea and requirements will be more willingly adopted unless someone thinks they have a better idea, a process that should be encouraged. We have experienced too often however managers who arrive with a complete and non-negotiable set of plans for the future and set about implementing them without any consultation or explanation.

Looking for 'buy-in' from their staff has another advantage for the manager. It is likely that those existing staff members who do not share the manager's vision will start to look for alternative employment without any further prompting. In our experience it is surprising how quickly it is possible to separate the staff who are part of the solution from those, usually far fewer, who were part of the problem.

One matter needs to be addressed with the station owners at an early stage. Does the station name need to be changed? Essentially the manager must ask whether the station branding has become so tarnished by poor performance that it would be better to start again with a new name. Or sometimes a proposed change of format or target audience may be sufficiently great that a new name becomes more appropriate, as is the case where local stations become part of a national group carrying similar programming, for example the newer Heart FM stations.

However re-branding is not always the best answer. One of the authors once nearly made a terrible mistake when suggesting a change of name to a local radio station. The commercial radio station for Harrogate in North Yorkshire had grown out of a community radio initiative and had been broadcasting under a commercial radio licence for around a year when it became clear a change of direction and management was needed. Coming new to the station it seemed that this would be an ideal time to change the name of the struggling station from Stray FM. Pointing out to the board of directors that the dictionary definition of stray, including such terms as 'go aimlessly', 'isolated' and 'homeless friendless person', seemed to accurately describe the situation in which the station found itself, a new name was proposed. The locally based directors and owners of the station robustly and correctly pointed out that "The Stray" was 200 acres of land wrapped around the old town of Harrogate fiercely and passionately defended by the people of the town for whom it is a popular traditional spot for outdoor activities. The name Stray FM perfectly reflected a pride and interest in the station's target area and was not changed despite a complete overhaul of all other aspects of the operation. Stray FM became and continues to be a very popular and profitable local radio station. The station name, as in many cases, represents a great deal of heritage and brand vales and should not be lightly discarded.

It is tempting, when confronted by an under performing station, to immediately reach for a marketing solution. However the funds and resources available for marketing any radio service are not limitless and the manager is well advised to deal with other problems first. Indeed it may make sense to cease all marketing and promotion until such time as the product is functioning properly. For example the programme manager turning round a poor schedule should be allowed to bring in their new line- up and regular programme features, and given time to get them sounding great, before non-listeners are invited to sample the new sound through extensive off-air promotion. Particularly where the brand identity has not changed, previously disaffected listeners, customers or funders are only likely to give the station one more chance, so it is best to delay any big promotion of the new product until the manager can declare themselves satisfied with the station.

Motivating individual staff can be tricky during the regeneration of a damaged radio service, targets and expectations must be very carefully managed. It is unrealistic to expect sales income or Rajar figures to undergo a sudden spectacular step-change following a revamp of the station, but this is exactly what many individuals hope for. The manager should make it clear that continuing incremental improvement, month- on-month, year-on-year, is all that is expected or required.

Staff motivation, particularly in a struggling station, does not simply depend upon cash incentives and creative feedback. Improvements to working conditions and facilities can send a very positive signal that the company, group or organisation is investing in the future and supporting the efforts of its workers. Gradually deteriorating facilities send the opposite message. Given a budget for capital expenditure on studios and offices the manager can to advantage stagger the spending across the year, rather than attempting to improve every aspect of the building in one go. Not only is it easier to manage one building, re-decorating or re- equipping project at a time but the sense that some aspect of the operation is being improved every week can create a positive atmosphere throughout the organisation. Managing the timing of a simple lick of paint or a new door mat in reception can be a valuable tool in improving morale and motivation in a formerly ailing station at a fraction of the cost of widespread salary incentives.

Community radio impact assessments

The growing community radio sector has brought with it new approaches and tools for evaluating station performance and its longer term effects on the wider community - this is known as impact assessment. Clearly for community stations audience figures are not the only indicator of success. Research here focuses on short and long term impact of the station on stakeholders whether they are listeners, members, programme makers, partner groups in the target community or funders.Much of this research been developed by researchers and community media producers to evidence and evaluate the impact of 'media for development' projects in areas where issues like health education, poverty alleviation and regeneration are paramount. The methods tend to put the users of the projects or stations at the heart of the research so that they are empowered by the process itself. An example of this is a methodology called 'ethnographic action research' (Tacchi, Slater and Hearn 2003)which uses methods such as field notes, in-depth interviews, group interviews, participant observation diaries and questionnaires (see also Slater, Tacchi and Lewis 2002). Birgitte Jallov (2005) developed a 'bare foot' impact assessment methodology with members of community stations in Mozambique. She developed a wide range of monitoring tools and techniques so that they could evaluate three levels of impact: whether the station itself was operating effectively and for the good of all those who were participating in it; whether the programmes were considered to be effective; and how of both of these affected development and change the community. (See also the comprehensive bibliography of this area compiled by Alfonso Gumucio Dagron 2006.)

In many cases the stations themselves are encouraged to develop a 'research culture' and focus on the kind of questions they need to explore and the kind of evidence that will be most useful to them. At Radio Regen volunteers have been used to help the station conduct research through collecting evidence for case studies of the impact on station members and groups they work with. Some stations are using blogs and user generated content to do this. (Radio Regen 2007) In a web chat about demonstrating audience impact, Phil Korbel summed up how and why community stations should value this kind of research:

It's clear that we should be doing research as a vital component of our sustainability, and that it should be built into the fabric of the everyday activity at a station rather than being an add on. It works to build our case as a sector and for stations to get money. Listener figures are important - but we should look at impacts and qualitative approaches too - to back the idea that our different relationship with our audience pays dividends to funders.

(Radio Regen 2007: 7)

Go to main page