Summary

In this chapter we outline the principles and

techniques of audience research including qualitative and

quantitative methods and techniques and how to understand and

interpret Rajar (Radio Joint Audience Research Limited) surveys.

We look at some critical perspectives on audience research

methodologies and some of the problems of audience measurement

for small-scale and community stations. Finally we discuss what

radio managers might learn from media academics.

Introduction

On a visit to RTV Chipiona, a publicly funded

radio and television station in a small coastal town in southern

Spain we were interested to see the station layout - a radio

studio and news office upstairs and a small TV studio and control

room downstairs. We talked to the manager about his target

audience. He told us that people in the town only listened to

local radio in the mornings so radio was broadcast until

lunchtime and then the local television took over in the

afternoon and evening. This manager knew his audience and their

media habits. For a small station with just a handful of

employees it was provident for him to manage his station in this

way.

Another example of the value of audience research comes from Andy

Parfitt, controller of BBC Radio 1 since 1998, who has detailed

knowledge about the importance of music in the lives of the

network's audience: 'I know what a 20 year old is doing

on a Saturday night; what music they get ready to go out to, what

they play in the car, what they fall out of a club at 3 in the

morning to...' (Born 2004: 264).

Audience research is 'designed to measure, define, construct

and ultimately build, audiences' (Tacchi 2001:156).

Throughout this book we refer to the needs, wants, tastes,

expectations and habits of the target listener as the benchmarks

for decisions on everything from the editorial policy to the

technical means of delivery. As a result audience research, of

whatever form, is a crucial tool of the radio manager. The target

audience is initially defined from a study of the existing

market, into the un-served needs of potential listeners, then,

once the service is up and running, it must periodically be

checked to see if it is, in fact meeting those needs.

Is there a typical listener?

Most programming consultants recommend to their client stations that they develop a detailed profile of a mythical 'typical listener', complete with name, age, hair colour, job and family background, and train the presenters to visualise that person as they speak. US-based radio consultant Ed Shane (1991: p80) says:Choosing an individual creates a focus of attention that helps a skilled on-air performer utilize radio's power as a one-to-one medium. The idea of using this type of attention focus is to create a metaphor for the entire audience. Since there are no pictures, no illustrations, no printed words, radio relies upon the private link between what is broadcast and the listener's imagination and interpretation. We ask announcers to visualise their typical listener as if that person were sitting right there in the control room. When the image is clear, we tell them, talk to that person in a natural, conversational way.An example of this from the 1980s saw commercial radio presenters encouraged by managers to target 'housewives' thereby contributing to the stereotyping of all female listeners as a housewives and potentially ignoring other sectors of the audience:

We call our average listener Doreen. She lives in Basildon. Doreen isn't stupid but she's only listening with half an ear and doesn't necessarily understand long words.Since 2005 BBC managers have encouraged presenters to personify the typical BBC local radio listener as 'Dave and Sue':

(Baehr and Ryan 1984: 37).

Dave and Sue are both 55. He is a self-employed plumber; she is a school secretary. Both have grown-up children from previous marriages. They shop at Asda, wear fleeces and T-shirts, and their cultural horizon stretches to an Abba tribute show. They are "deeply suspicious" of politicians, think the world is "a dangerous and depressing place", and are consequently always on the lookout for "something that will cheer them up and make them laugh".The technique of profiling your supposed audience can be useful commercially and in terms of communicating but the risk is that you can alienate others. Barnard quotes one presenter's discussions with his programme controller about the target audience for his mid-morning programme:

(quoted in Self 2005: 33).

From our discussions I gathered he wanted to go for the housewives. And so we did. But people kept saying 'there's 20 per cent unemployment in Coventry - shouldn't you be catering for the male listener at that time of the day?' ...But I remained totally sexist in a pro-female way, and it worked. The increase in the JICRAR was quite appreciable.(Author's note: JICRAR (Joint Industry Committee for Radio Audience Research)produced commercial radio audience ratings until 1992 when Rajar was established jointly with the BBC)

(Barnard 2000: 130)

At the BBC 'Sue's' profile was changed a few years later, now she is targeted as being on her own (Kelner 2008) and the expansion of community, digital and other commercial radio channels has meant that audiences in Coventry now have a choice of ten channels, including two community stations and two stations aimed at Asian and Punjabi communities.

Qualitative and Quantitative Methods

Managers use a wide variety of research techniques to find out about their listeners but these can usually be divided into two distinct categories, qualitative research to test attitudes or quantitative research to measure habits. Qualitative research tells the manager about listeners' attitudes, their tastes and their perceptions. It can indicate which songs they want to hear, which presenters they prefer, their interests in local news etc. The numbers are not important, the manager is looking for clues which will help her or him to plan their programmes. A discussion group of ten target listeners might generate enough material to keep the programme team busy for months. Qualitative studies are research in depth rather than breadth and it is more important for them to be carried out well than with a large number of respondents. Often they are best conducted with non-listeners than with listeners!Quantitative research, as the title implies, involves counting things: How many people listen to this radio station? Are there many in this or that part of the region? How many go to the cinema or enjoy cookery? For these answers a simple, carefully worded, questionnaire placed in front of as many of the right people as possible gets the most reliable results.

Quantitative radio research used to be very simple. If the BBC wanted to know how many people were listening to its radio programmes it stopped a few in the street and asked them what they remembered listening to the previous day. It was relatively cheap, it was straightforward to undertake the research and process the results in-house and it gave the BBC both the quantitative and qualitative results which it needed to justify its public service role.

Rajar and Listening Diaries

From the start of commercial radio in 1973 it was clear that the stations needed more precise information about times and durations of listening to convince advertisers to spend money. The Joint Industry Committee for Radio Audience Research (JICRAR) chose the "listening diary" methodology, using a booklet in which each radio station in a given area was given a column and people marked which stations they had been listening to each quarter of an hour through the day.Inevitably, given the methodological differences between the two methods of audience measurement, the BBC and the commercial radio sector often produced conflicting results. It was clear that, in order to gain the trust of licence payers, the government and advertisers alike, a single agreed system would be needed.

Since 1992 listening diaries have been issued and the results analysed under contracts awarded by a company jointly owned by the BBC and commercial stations, Radio Joint Audience Research Limited, commonly known as Rajar. The company is now jointly owned by the RadioCentre (the trade body representing the Commercial Radio stations in the UK) and the BBC. With each body owning 50 per cent impartiality between BBC and commercial interests is protected, policy decisions requiring the agreement of both parties and representatives of the advertising industry who also sit on the board.

A total of 130,000 respondents are used each year making Rajar the biggest audience research survey in the world outside the USA. It is also one of the most complex consumer surveys. Results are produced for about 340 separate radio services, including 60 BBC stations, but few of them cover exactly the same area as another station (Total Survey Area or TSA) so, allowing for overlaps, data have to be analysed for more than 600 different listening areas across the Great Britain and Northern Ireland.

Respondents are each asked to complete a one week diary showing all the stations they listened to, for at least 5 minutes, recorded in quarter hour time blocks. The results are published every quarter for all the stations, although for the smallest stations the figures are based on a rolling sample taken across the previous 12 month period.

While Rajar controls and commissions the survey the actual work is undertaken by market research specialists. Under a two-year contract starting in 2007 Ipsos MORI undertakes the fieldwork while sample design and weighting is handled by RSMB Television Research Limited.

Every three months the latest top line results, weekly reach and hours listened per station, are made available to the public free of charge, most conveniently via the Rajar website www.rajar.co.uk, only participating stations and other subscribers have access to more detailed information on each service. Many smaller commercial stations and community radio services cannot afford to participate (costs typically start at around �7,000 per annum) and are not included in the survey.

While the present system has served radio well, it has inherent shortcomings: It does not produce listening figures for a particular programme on a particular day, only an average of the audience for that time slot over three, six or twelve months; there is no reliable way of telling how someone listened to a particular programme - on AM, FM, DAB, over the Internet or via a podcast; and the time taken for data collection and processing, audience response taking months to reach a programme manager, is in sharp contrast to the immediacy of feedback available to internet-based media. In his detailed analysis of possible new radio audience research methodologies, Starkey (2003: 118) pointed out that many programmers: 'making even small changes to their schedule or their music policy, might prefer to see more immediate data in order to know how audiences are responding to the changes. Depending on how much they want to micro-manage their output, they may even want to consider reversing unpopular decisions before they cause too much damage to the station's market share.'

Under pressure from the then Chairman of The Wireless Group the former Sun editor Kelvin MacKenzie and others to find an improved system, in 2001 Rajar instituted a number of tests of automatic electronic listening 'meters'. At the time of writing a two year project is underway to test portable people meters in collaboration with BARB, the TV research body.

As most people listen to many different radios in different places every day, the people meter must be attached to the individual respondent. Competing systems include a wristwatch-style device that records samples of what its wearer hears, and sends this data back to a central computer overnight. The central computer is supplied with recordings of all the available broadcasts to compare with the information sent back by the meter and thus analyse to which stations it was exposed.

A rival system depends upon participating stations including sub-audible coded signals in their programmes. The pager-like people meter records these codes and returns them to the central computer for processing. works by recording a special inaudible code transmitted alongside stations' programmes. An advantage of this method is that, by inserting different codes, the meter can distinguish between the same programming delivered via different platforms (FM or DAB for example) and might be able to pick up delayed listening to podcasts and downloads. However it will not record any listening to non-participating services.

Many questions remain to be answered before the industry will dare to switch from its present 'gold standard' Rajar to a new system. There are questions of cost, practicality, user compliance and how to measure personal headphone listening for example. And any new methodology will inevitably result in a step-change in reported listening for at least some broadcasters.

How to read audience figures

Only if everyone were listening using a digital device with a return path, and only if they all agreed to supply the information, would we ever know exactly how many receivers were accessing our service at any one time. Even then we would only know that the device had selected our programme, we would have no idea how many people, if any, were actually listening to it.As with Rajar, the only practical solution is to select a group of potential listeners and take their answers as representative of the whole relevant population. If we have enough of them, and are careful with the age, gender and demographic makeup of this smaller group we can call them a representative sample. The smaller the group, no matter how well balanced, the greater the margin for error and the greater the need for caution in interpreting the results.

Statisticians talk of a "confidence interval", a range of possible answers that runs from a figure lower than the result given to a figure higher by the same amount. For example according to Rajar (Rajar/Ipsos MORI 2005: 781) a result of 50 per cent from a sample of 500 respondents has a margin of error of plus or minus 7 per cent. That means a reported 50 per cent figure could in reality be as low as 43 per cent or as high as 57 per cent. This is described as a "95 per cent confidence level", meaning that the figures will fall within this range 95 times out of 100.

If that does not seem accurate enough it is instructive to look at the sample size needed for greater confidence in the data. In order to reduce the margin of error to within two percentage points the sample size would have to be increased tenfold to around 5,000 respondents. With most data now being electronically collated and tabulated the largest part of the cost of any survey goes on the fieldwork and these costs are almost directly related to the desired sample size. Nobody is going to spend some ten times more just to improve their confidence in the data by a few percentage points. These sample size considerations are just as relevant to electronic metering as they are to the traditional "diary" or questionnaire methodologies.

Even if the total sample for a survey is 800, a perfectly respectable sample size in most applications, an individual age band or other demographic cell in the published results will have been derived from a much smaller number of respondents. Where we wish to study the results for this smaller group the confidence interval is defined by this smaller number.

For example, a typical Rajar sample of 507 adults in a small local radio area (Rajar/Ipsos MORI 2006) was actually made up as follows (prior to weighting the data to match the local population profile):

|

Age: |

Number of men |

Number of women |

| 15-24 | 36 | 40 |

| 25-34 | 35 | 29 |

| 35-44 | 30 | 53 |

| 45-54 | 37 | 37 |

| 55-64 | 45 | 61 |

| 65+ | 42 | 62 |

These issues are even more pressing where the entire service is aimed at a group who represent some minority within society. When Kelvin MacKenzie set up the 'Little Guys Radio Association' to challenge the commercial radio trade body over Rajar methodology, arguing that it represented the interests of only the major groups, it was significant that the other stations which felt motivated to join all targeted identifiable minority communities or interests. Founding members included Premier Christian Radio, Club Asia, Spectrum Radio and Sunrise Radio all of whom saw audience figures fluctuate according to the number of diaries given to their target audience group, a variable not corrected for in the Rajar sampling and weighting mechanisms.

Sunrise Radio Chairman Avtar Lit was quoted as saying: 'The Asian community is grossly under-represented in the Rajar survey and the audience figures for stations such as Sunrise Radio have been under-reported under the diary system for many years. We have been campaigning for years that the Asian community should have more diaries in the Rajar survey' (Radio Magazine 2002).

While the Rajar methodology can be described as the "least worst system" available at the present time and gives a robust sample size for reliable assessment of overall station popularity, it is crucial that we become more sceptical of the data as we slice them more thinly.

Despite any concerns over the reliability of data, programme managers are regularly called upon to review the performance of individual programmes using audience figures. This can be undertaken with greater confidence by using comparisons with other data. Given a set of numbers in isolation, even with the most robust sample, it is not possible to say whether they represent "good" or "bad" performance.

Any research result should be interpreted in relation to at least one other piece of data, preferably several if the sample sizes are small. In analysing the results for a single programme suitable benchmarks might be:

- Previous performance of this service at the same time and

day.

- Performance of competitors' services at the same time and

day.

- Performance of comparable programmes, perhaps on similar

group-owned stations, at the same time and day

elsewhere.

- Overall size of the total radio audience at this time on this

day.

- The average audience delivery of this service at all other times.

To be fair the manager can only say that a programme is doing well or badly if it is moving in the same direction in relation to at least two or three of these benchmarks. Even then, of course, the change may be due to unavoidable external factors over which the manager and the programme staff have no control.

Many managers believe that trends over three or more surveys are more important than any quarter's individual results. They argue that it takes time for listeners to adapt to any change and that the most recent results probably reflect the audience getting used to changes made a year previously. Experienced programmers know that it can take as short a time as fifteen to twenty seconds for an existing listener to switch off if you offer them something they do not like, conversely it could take fifteen to twenty months before a non-listener becomes a regular listener because of that same programme change!

As in all aspects of a manager's dealings with employees it is important, in discussing research findings, not to dwell on the negatives. In a creative field like programming it is better to seek out the most successful aspects of the schedule, analyse these, praise the people who did well and apply the lessons learned to the weaker points in the day. The manager must avoid spending all their time worrying about the things which apparently did not have the desired result but rather should investigate the items that worked well in as much detail as those that did not. Better to focus the minds of the team on what success sounds like than to endlessly recount their failures.

Audience research terms

When reporting the overall performance of a station the main factors used are weekly reach, average hours, total hours and share, and are defined by Rajar (2008) as follows:Weekly Reach

Defined by Rajar (2008) as: 'The number of people aged 15+ who tune to a radio station within at least one quarter-hour period over the course of a week. Respondents are instructed to fill in a quarter-hour only if they have listened to the station for at least 5 minutes within that quarter-hour. Between 24.00-06.00, listening is recorded in half-hour periods.' The weekly reach, and population size, is usually expressed by in Rajar table as a number of thousands.Weekly Reach per cent

'The Weekly Reach expressed as a percentage of the Population within the TSA' (Rajar 2008). Note that the total of the reach figures for all the stations in an area will greatly exceed 100 per cent as most people report listening to two or three stations each week. This measure indicates which station in a market has the most listeners - but gives no idea how long they stay with the station.Total Weekly Hours

'The total number of hours that a station is listened to over the course of a week. This is the sum of all quarter-hours for all listeners' (Rajar 2008).Average Hours

'The average length of time that listeners to a station spend with the station. This is calculated by dividing the Weekly Hours by the Weekly Reach' (Rajar 2008). Of great interest to programmers this is the key measure of loyalty to your station - how long does your average listener listen for in the average week. Typical results for local stations are in the range of seven to ten hours, suggesting that the average listener listens to that station for between one and one and a half hours on an average day.Market Share

'The percentage of all radio listening hours that a station accounts for within its transmission area. This can be calculated for any target market across any area' (Rajar 2008). This is the measure, combining both the number of people listening and how long they listen for, that is most properly used by stations to show their position in the market. To be 'the most listened to' or 'number one' station in a market a station's market share should be greater than any other station's measured across the same market.A station specifically targeting a particular demographic might extract the relevant data just for their target group in order to claim to be, for example, 'number one with women over 35'

Defining the station's coverage area

The Total Survey Area (TSA) is the area within which a station's audience is measured. Unlike the Measured Coverage Area (MCA) used by Ofcom, which is derived from calculations or measurements of actual signal strength, stations may choose their own TSA. Rajar rules require that it must be a contiguous set of postcode districts (the postcode district is the first part of the postcode, in AA1 2BB it would be the AA1 section) but set no other limit. Postcode maps can be obtained using various software applications and may be purchased from stationers.For regional and national services defining a map this way is quite straightforward, but the coarse grid of postcode districts can pose dilemmas for a very local service. A station claming too many postcode districts will appear to cover a larger population but if the signal strength and editorial proposition of the station does not adequately fill the area many of the more remote diary respondents will not even consider the station and the resulting percentage weekly reach and share figures will look very poor. Conversely a station claiming too small a TSA will not only appear to serve much fewer people, but any listening outside the TSA will not be included in the station's Rajar report.

This is most acutely felt where a major centre of population falls just outside the main postcode districts of a TSA but where the addition of the whole extra district would distort the local proposition of the station (see below). It is necessary to consider both the projected transmitter coverage (a signal strength map will have been produced to support the licence application) and the social tendencies of people in the postcode district in question, asking if they will be able to hear the station and, if so, will it interest them?

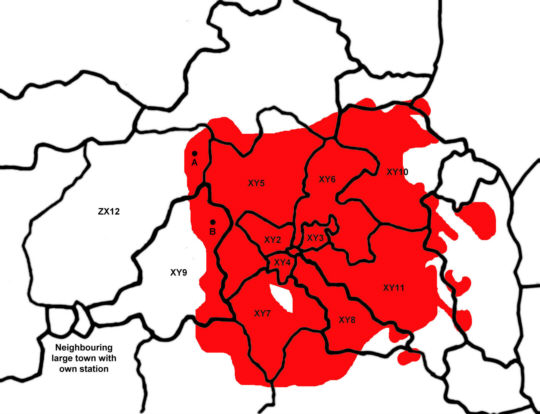

Typical local radio map - showing coverage with a good stereo signal against postcode boundaries.

In this example the signal coverage prediction (in red) suggests we should include postcodes XY1 (in the centre of the city) to XY8 inclusive, and also XY10 and XY11. The question is whether to include the towns labelled A and B in our TSA. If we encompass these towns in our marketing area we will also be surveyed throughout districts XY9 and ZX12, both of which stretch right up to the nearby city where listening is dominated by a different local station. This larger population coverage might make us appear less successful (in terms of share and reach percentages) in our core area.

Note that postcode districts tend to be geographically smaller in areas of dense population but can cover vast areas of unpopulated countryside. Until the Rajar map was simplified in 2007 TSAs were defined using the smaller units known as postcode sectors, which enabled more precise targeting of the research but made the fieldwork far more complicated.

Other research

Where a Rajar survey is not practical or affordable, or when a station needs more specific information on the tastes and habits of potential listeners, the manager may be expected to commission their own research project.A great deal of useful information can be obtained from simple research initiatives which the station can mount in-house, often using telephone research or a response mechanism via the station's web site. However, where the results are to be used to impress outside bodies such as advertisers, sponsors, supporters, Ofcom or the press it is usually necessary to commission a reputable research company to undertake the fieldwork and data analysis. The researchers will recommend as appropriate methodology and design the questionnaire, but the manager has to decide what questions are to be answered by the study.

Firstly the manager must be clear who he or she is interested in hearing from. There is no point in interviewing a balanced sample of people of all ages if we are planning a service that aims to succeed with teenagers. Just talk to the potential core audience: Who are they? Where do they live or gather? Secondly, given that respondents will only answer a few questions, the manager must focus on what exactly they must be asked about. Are we interested in their present habits, what they actually do with their lives, their radio listening, shopping, Internet useage? Or are we interested in their attitudes and beliefs, tastes in music, feelings about current radio programmes?

The techniques of market research are outside the scope of this book (see Hague, Hague, and Morgan2004), but from time to time the radio manager will have an opportunity to put a question before a sample of the audience, or potential audience. It is worth taking the time to word such questions very carefully, and to allow an adequate range of responses. In particular the results may be invalidated if the study uses leading questions.

For example it is tempting to ask: "Do you agree that XXX FM is the best radio station?" Far more useful data would be achieved by saying: "Look at this list of radio stations that can be heard in this area. Could you tell me which one you personally listen to most often?" It is quite possible that the service perceived as 'best' may not be the station they most often listen to in practice. And when asking about listening habits it is important to include a time scale: "Which of these stations do you listen to?" should become: "In the last seven days, which of these stations have you heard?"

If anyone is going to take the results seriously the methodology should avoid revealing who has commissioned the survey until that information cannot influence the results significantly. So a manager wanting to know more about a specific station, their own or a competitor, should leave those specific questions to the end, after any questions on general media habits and overall radio listening.

Focus groups

The real value of research lies in what it tells about what we should be doing in the future, rather than in its ability to give numerical values to what we have done in the past. In order to make good decisions for the future the manager needs to know about the perceptions, attitudes and feelings of their target audience. A handy and effective way of identifying such qualities is the focus group. Essentially a discussion between a small group of carefully chosen members of the public and a researcher usually referred to as a 'facilitator', lasting perhaps two hours, the focus group is encouraged to talk freely and openly about the matters under consideration. The members, typically between 6 and 12 in number, might be played recordings of particular stations, presenters or music and invited to express their feelings about them. Much of the success and value of focus group research comes from the skill of the facilitator in gently leading the discussion, they should not have an axe to grind and are usually an independent professional researcher. While the session will be recorded - with the participants knowledge and consent - and might even be viewed by station management on a video monitor or through a one-way mirror, it is important that the station is not felt to be present in the room in order to avoid any psychological pressure on the group.Particularly valuable in establishing perceptions about the actual or proposed programming or marketing of a radio station, the focus group can provide the manager with valuable insights into the ways people relate to the station and its competitors and thus with that most valuable commodity - ideas.

It is tempting to see the focus group as a cheap alternative to a questionnaire based survey, but in reality the careful selection of participants - to ensure they are representative of a certain group of listeners, ages or lifestyles - can require substantial effort. A good researcher is also required to provide a useful and fair interpretation of what the group said.

Music testing

The pseudo-scientific, some would say cynical, approach to music selection by many of today's top radio companies causes no end of heated debate both within and outside the industry. However the restricted playlists of many stations are based on a simple premise with which it is hard to argue: when one of your target audience switches to your station you want to be playing a song they want to hear.Worldwide commercial radio experience shows that stations that focus on the strongest, most appealing songs do better than those who don't. The aim of music testing is to establish which songs a station's target audience do and don't want to hear on the radio. Note that this is different to researching which songs they appreciate, sales and download charts measure something quite different, many highly popular songs suffer from "burn" - listeners are simply tired of hearing them. It should be no surprise that stations that avoid playing songs their target listeners dislike hearing on the radio can gain far higher hours of listening and therefore a larger market share.

Music testing is usually undertaken using a large number of extracts, "hooks" typically around 8 seconds in length, of familiar songs which the station already plays or might select in future. Such short samples have been established as adequate for the majority of listeners to identify the song and express an opinion on it and are far more effective than simply giving the participant a list of titles and artists, most of which will not seem instantly familiar. For each audio clip the listeners are usually asked to give a score, perhaps on a scale of one to five, of how much they like the song and, separately, how much they would like to hear it on the radio.

While such research can be undertaken over the telephone, by posting out recordings or using web-based tools, the most commonly method has traditionally been to conduct an Auditorium Music Test where a precisely recruited group of a hundred or more listeners or potential listeners is assembled in a meeting room. Over a period of an two or three hours, with breaks, they are played numbered clips and asked to score them on a paper form or, increasingly, using a hand-held electronic device. It is possible to test over 400 songs in a single session.

The results are tabulated and the station receives a report showing the relative popularity of the music, often using a proprietary computer program to combine the popularity and "burn-out" scores into a single league table. While experience suggests that listeners' musical preferences do not change rapidly with time, repeated testing of songs the station is playing is advisable at regular intervals - perhaps annually - to check for burn-out, changing fashions or the fall from grace of a previously well loved artist.

Such testing is a major exercise and most stations cannot afford to undertake it frequently, if at all. Fortunately, identical tests around the UK have established that musical preferences do not vary greatly from region to region and larger radio groups commonly undertake a single central test to inform the playlists of all their same-format radio stations. Auditorium testing is also too blunt an instrument to help the programmer with the selection of new or recent releases. Not only is it held too infrequently but it assumes the majority of respondents are already familiar with the tune. Here there is still scope for the inspired skill of an experienced programmer, although often supported by the auditorium results of similar material in the past and an opportunity to gain listener feedback via the station's website or weekly "call-out" telephone research.

Research for community stations

Community radio is a different animal when it comes to research because on the whole stations are not as interested in gaining mass audiences but rather serving particular audiences within their schedule and being a tool for social action and community development. Few stations are able to afford, or want to be to be part of, Rajar but that doesn't mean that they are not interested in knowing more about their audiences and some have found new ways to do this. In community radio developing new audiences is about the importance of strategic and social partnerships. It is also very important for community stations to be able to provide evidence of 'social gain' to funders.Phil Korbel, director of Radio Regen, summed up a discussion about community radio audience research:

It's clear that we should be doing research as a vital component of our sustainability, and that it should be built into the fabric of the everyday activity at a station rather than being an add on. It works to build our case as a sector and for stations to get money. Listener figures are important but we should look at impacts and qualitative approaches too - to back the idea that our different relationship with our audience pays dividends to funders."Dominowski and Bartholet (1997) have designed a useful on line resource called 'The listener survey tool kit' for community stations that has a wealth of information related to building a survey, choosing appropriate methodologies and questions, processing, analysing and reporting data. It also has a very wide range of examples of 'off the peg' questions that could be adapted by community radio audience researchers.

(Manchester, Scifo and Korbel 2007: 2)

Crucial to community radio station managers is assessing the impact of radio as a tool for social purposes. We will look at tools for this in Section 2.12.

New approaches to radio audience research

In recent years academics within university radio and media departments have carried out research into specific audience behaviours and trends, both independently and in some cases collaboratively with radio stations. Academic research has employed a range of ethnographic techniques 'to chart the sense that media consumers make of the texts and technologies they encounter in everyday life.' (Moores 1993: 1). An example of this a research project funded through the Arts and Humanities Research Board (AHRC) called the BBC / AHRC Knowledge Exchange Programme: which is looking at listener on-line engagement with BBC radio programming, including the long running Radio 4 soap opera 'The Archers'.In Jo Tacchi's ethnography of listening habits (2000) she spent three years observing role of radio in domestic life and relationships. She carried out in depth interviews, participant observation, observation at local listener panels and focus groups. She uses this material to gain a deeper understanding of how radio sound fits in with people's lives, including possible gendered differences.

Sara O'Sullivan carried out research on one of Irish radio's most popular daytime talk programmes on RTE 1, she looked into the way that phone-in callers participate and 'perform' in air and their relationship with the show's host and the listening audience (O'Sullivan 2005).

Lyn Thomas researched the appeal and audience of the long running BBC radio soap 'The Archers' through questionnaires, in depth interviews and focus groups. She carried out some of this research at 'Archer's Addicts' fan conventions and through ' the 'official Archers' fan club' and through these methods gained valuable insights into the way people associated the programme with 'pleasurable rituals of everyday life' (Thomas 2002: 136).

Finally, Stefanie Milan's research into what makes community radio practitioners happy provides an insight into the lives and motivations of community producers who area also audience members (Milan 2008).

Go to main page